publishing 101: a survival guide for children’s book illustrators

Most of you know that I started out in children’s book publishing — my first jobs in the industry were as a picture book illustrator and a book designer for Dial Books for Young Readers. Though my career has diversified considerably since then, when it comes to publishing I’m most often asked about illustrating and writing children’s books. (Publishing tarot decks are a close second.)

It’s easy to give people the basics. But what about those who have sold their first book or two? Where do they go from there? In these competitive times, should they just be grateful to be published?

My two cents: be grateful for all you’ve accomplished — and aim to grow. With this in mind, here is a short guide for actually thriving (not just surviving) as a children’s book illustrator.

Promote yourself. If you were an agent for another artist, how hard would you market their work to other publishing houses? Most likely harder than you are promoting your own art right now. Most people (myself included) have a real block when it comes to getting out there with their work. After all, we’d all rather be in the studio working than deal with the business end of things. A good exercise in getting past this is to pretend you’re marking someone else’s work, an incredibly successful and gifted artist. Now, what would you do?

Feel the difference? This is how hard you should be marketing yourself.

Are you sending out mailers regularly? By regularly, I mean three or four times a year, not every decade. Make sure your mailing list is up-to-date. I prefer the Literary Marketplace (LMP for short) because I find it more accurate. Read Publishers Weekly to see what editors are moving where, which houses are actively acquiring books. Get on the phone and call a publisher to find out what editor acquired a book you love. Confab with your colleagues with the biz — if you don’t know any, join SCBWI. However you do it, do it. How else will editors and art directors find you?

What about your website? Does it accurately reflect your current work? Is it professional looking? Can art directors and editors easily contact you via it? Give at least two ways to contact you, in case one way isn’t working. E-mail goes down, phone lines go kaplooey — but your business doesn’t have to.

And don’t forget school and library appearances and book signings. They’re all good ways to to gain publicity for your work, and are a good antidote to artist’s isolation. Some illustrators make a nice income from school appearances alone — but that’s a whole other subject.

Expand your markets. It’s tempting to work with only one publisher, especially if they were the one to discover your work. Loyalty is a wonderful quality, especially in monogamous relationships. In authors, it cuts both ways. The realities of publishing preclude a house from publishing more than one of your books a year at the very most. Average book advances being what they are, can you really afford to do that? Plus, what if there were delays while you’re working on a book? Would it be good to have another book to work on while you wait?

These are only some of the reasons I think illustrators should work with more than one publisher.

Diversify! As a children’s book illustrator, you have a unique position of being able to sell yourself as an illustrator of manuscripts and as an author. If you are marketing yourself only as one of these, you’re missing half your income.

To sit around and wait for an editor to find you a manuscript is unfair to your art. It also makes the editor responsible for your career — you probably know better than others what book you’d like to illustrate. Likewise, it’s foolish not to work on someone else’s manuscript because you didn’t write it. A book is a book and will only help your career grow.

Some illustrators feel unable to write for publication. One solution: common property material. Common property is when the copyright expires on published material, meaning it can be reused without paying the author. Dover Books bases their entire list on repackaging common property material; Grimms Fairy Tales, Blue Fairy Book, and much more are common property.

You can also think of ideas for books and propose them to a publisher. Way back when, my first two picture books were sold from proposals and sample illustrations; my editor then hired an author to write the manuscript to accompany my art.

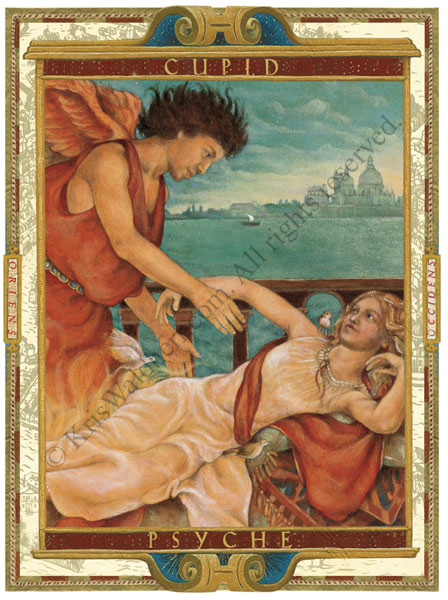

Crossmarket your art. I hope you’re not ignoring your book art after it’s been published. There are other markets awaiting it!

Greeting card companies sometimes use children’s book art. Some pay a flat fee, while others pay a royalty based on sales. All will include sample cards to you as part of your agreement, which is a nice promotional item to send publishers and other potential clients. If your artwork is suitable, there’s also posters, calendars and day books, even novelty mugs and plates. (Whether you like her work or not, Mary Engelbreit has based an entire merchandising empire on these principles.)

One caveat: Make sure to reserve merchandising rights when you negotiate your book contracts. Most publishers don’t mind, since they rarely exercise these rights. If there is an issue, sometimes it’s because publishers fear competing products — clarify in your contract that these rights will only be exercised if they do not materially interfere with the publisher’s selling of your book.

There’s also the fine art world, if your art isn’t digitally created. Seek out galleries that specialize in exhibiting and selling illustrations, or participate in local art shows. If you do decide to sell your original art, make certain you have a high quality scan before you part with it—that way you can always reproduce it in the future.