Interview with author Kathleen Williams Renk

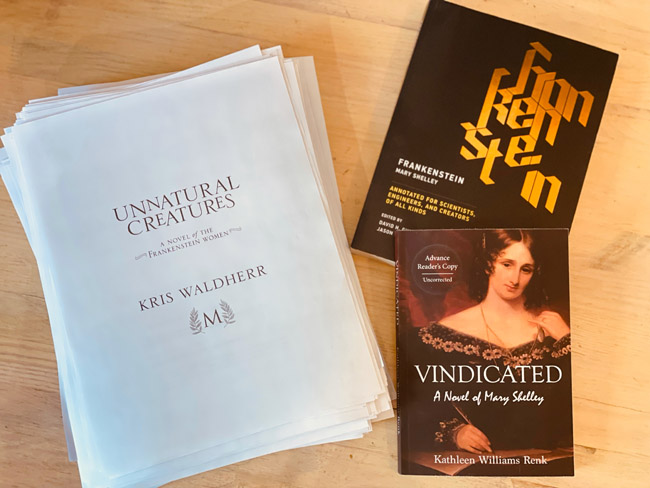

First page proofs of Unnatural Creatures next to two book friends. Don’t they look cozy?

First page proofs of Unnatural Creatures next to two book friends. Don’t they look cozy?

I’m delighted to welcome Kathleen Williams Renk to my site today! I was so pleased to receive a copy of her novel Vindicated, an intimate portrayal of the life of Mary Shelley that I devoured in a matter of hours. If you’re as fascinated as I am with Shelley and her circle, you won’t want to miss this book. In our interview, Renk and I chatted about her writing process, research, Mary Shelley and her family, and more. I was especially excited to learn that Renk is working on a novel about Christina Rossetti and Elizabeth Siddal—read on for the details.

* * *

Kris Waldherr: Vindicated is presented as a series of journal entries throughout Mary Shelley’s life. While most of the entries are Shelley’s, you also included a few from her parents, Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin. What inspired you to choose this narrative structure, instead of a more conventional novelistic one with scenes and chapters? What challenges did it present? I wondered if it was tricky because Shelley’s journals and letters have been published.

Kathleen Williams Renk: Initially, I began the writing of the novel with these alternating voices of Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin, because, when I was in grad school at the University of Iowa, I read Godwin’s memoir of his wife and I was most struck by the circumstances of Mary Godwin’s (later Shelley) birth and how physicians had brought puppies in to nurse Mary Wollstonecraft’s breasts rather than having her own daughter nurse. As a former Obstetrics R.N., I knew how truly bizarre this was; this was no cure for a retained placenta, which is what Mary Wollstonecraft suffered from and what killed her eleven days postpartum.

Kathleen Williams Renk: Initially, I began the writing of the novel with these alternating voices of Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin, because, when I was in grad school at the University of Iowa, I read Godwin’s memoir of his wife and I was most struck by the circumstances of Mary Godwin’s (later Shelley) birth and how physicians had brought puppies in to nurse Mary Wollstonecraft’s breasts rather than having her own daughter nurse. As a former Obstetrics R.N., I knew how truly bizarre this was; this was no cure for a retained placenta, which is what Mary Wollstonecraft suffered from and what killed her eleven days postpartum.

Overall, the choice of writing journals in the voices of these characters seemed quite natural. I had read Mary and Percy’s joint travel journal, which Percy eventually abandoned, but Mary’s entries read like travel itineraries of travel and contain lists of books that they read. The entries do not include emotional or personal experiences. I wanted to give Mary Godwin Shelley a voice and demonstrate that she was more than the author of Frankenstein. I wanted to show that she was a grieving teen, a child who never knew her mother, that she herself was a mother who had lost three children, that she was a widow who sought to redeem her husband’s literary and personal reputation, that she was a writer who supported herself and her one living son, Percy Florence, and that she was justified in having lived when her mother had died giving birth to her.

In terms of challenges, I tried to make her voice sound authentic for the time and for her education and lineage, since she was the daughter of two famous and rather infamous British philosophers. I also didn’t want Mary’s parents’ and Percy’s literary legacy to overshadow Mary Godwin Shelley’s so, even though it was necessary to speak of their work, I tried to keep Mary’s writing at the forefront. Plus, it would have been easy to make Mary wallow in grief for all of the tragedies that befell her but knowing that creative work and scholarship helped her cope with losing her children, her half-sister, and Percy, I always returned her to her pen. Her work, guided by her mother’s hand, gave her solace.

KW: I loved how you explored Mary’s relationship with her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, who died soon after giving birth to her daughter. In Vindicated, Wollstonecraft literally haunts Shelley’s waking and dreaming life. Can you talk a little about this?

KWR: Having read several biographies of Mary Shelley, particularly Muriel Spark’s Child of Light, I knew that Mary often visited her mother’s grave, and it seemed to me that she would naturally wish to speak with her mother, so I imagined conversations with them where MW unwinds her shroud and speaks with her daughter, but also times when Mary Shelley dreams of her mother and asks advice about love and life. I hope that the reader discerns that some of these instances might be real or imagined on Mary’s part. In any case, because she sought to know her mother through her mother’s writing, she would seek her mother’s help with all things, including the writing of her novels. She certainly wanted to live up to her mother’s brilliance as a female philosopher and wished to be worthy of having “caused” her mother’s death.

KW: Your background is as a scholar of British, Irish, Postcolonial, and Women’s literature, and you have published scholarly books on that front. How does writing nonfiction inform your fiction? Is your process different for writing fiction?

KWR: I greatly enjoyed my scholarly work but have to admit that returning to writing fiction, which I also did in graduate school, is quite liberating. And, of course, writing historical fiction still involves a considerable amount of research, but then I get to imagine “gaps” in the biographies. My process is somewhat different in that I sometimes use writing prompts and write initially in the voice of a character, which leads me in new directions in the narrative.

Unlike some other fiction writers, I don’t outline a plot. Even so, I use some of the same methods that I used when writing nonfiction. I always know when I leave off for the day and how I’ll continue the narrative the next day. And, of course, as you know, as it is with nonfiction writing, writing is re-vision, not just doctoring errors, but seeing the piece as a whole and noting where more development is necessary.

In terms of the ways my scholarship informs my fiction writing, my second novel about Lizzie Siddal and the Pre-Raphaelites is the result of research I did for my third scholarly book, Women Writing the Neo-Victorian Novel: ‘Erotic’ Victorians (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020). The first chapter in that work focuses on women artists in Neo-Victorian novels seizing the artistic gaze. That led me to do quite a lot of research on women artists associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Movement. And, subsequently, I decided to write about Lizzie and her sister-in-law Christina Rossetti.

KW: I was excited to read that you’re writing about Elizabeth Siddal and Christina Rossetti as well as a novel about Shelley’s husband, Percy. Can you fill us in on what to expect from these books? (Side note: I am obsessed with Siddal, and actually visited her grave in Highgate to pay my respects.)

KWR: Thanks for asking about my other projects. Both of these novel projects are alternative historical fiction. The first is entitled IN AN ARTIST’S STUDIO and in it I pose these hypothetical questions: What if the Victorian poet Christina Rossetti’s sensual “Goblin Market” was based on her attraction to her sister-in-law, the poet/artist/model Elizabeth Siddal Rossetti? What if, instead of mutual antipathy, Christina and Elizabeth forged a friendship that led to love?

In an Artist’s Studio re-imagines the relationship between these two poets/artists, as revealed to Maggie Winegarden, an historian who stumbles upon Lizzie’s and Christina’s journals buried in the catacombs of St Clement’s Church in Hastings. The journals begin in 1845 and continue until 1862, the year of Lizzie’s untimely death from a presumed laudanum overdose. In them, Christina and Lizzie describe the trauma that they experienced, their desire for genuine love and affection, and their need to express themselves in poetry and art, despite being advised to avoid all intellectual and artistic enterprises. Eventually, these two artists find that they have great affinity for one another as they forge a Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood, where women artists pick up pens and brushes and create what Elizabeth Barrett Browning describes in Aurora Leigh – their better selves. It is within this women’s world that Christina pens her famous poem. Along the way, Christina must hide a shameful secret and Lizzie’s life is fraught with terror and sorrow as she is betrayed by the man who called her his “destiny.”

(As a side note, on a visit to Hastings in 2005, I stumbled upon St. Clement’s Church. I just went in to look around and saw Dante Rossetti’s painting of The Annunciation, where Christina posed as the Virgin Mary. I asked the caretaker about why it was in the church, and she said, “This is where Lizzie Siddal and Dante Rossetti were wed,” which naturally delighted me. I actually used that experience in creating the scene where Maggie sees the painting in the church).

The third novel is called NO COWARD SOUL HAVE I. In it, I ask why would Percy Shelley wish to meet the Irish rebel, Anne Devlin? No Coward’s Soul Have I creates an alternate history that explains Shelley’s fascination with and involvement in Irish rebellion against British rule.

Young Shelley has recently been expelled from University College, Oxford University for writing a pamphlet entitled, “The Necessity of Atheism.” It is 1812 and Shelley decides to begin his political life. He does not intend to become a Member of Parliament, like his father Sir Timothy, but instead he plans to aid the Irish in their fight for Catholic Emancipation and the repeal of the 1801 Act of Union of Great Britain and Ireland. And after that, he intends to free the entire oppressed world. With these unrealistic and lofty goals in mind, Shelley, his bride Harriet, and her sister Eliza Westbrook travel to Dublin. An admirer of the rebel Robert Emmet executed by the British in 1803, Shelley visits Emmet’s grave and encounters Anne Devlin, Emmet’s colleague, who was jailed and tortured for three years in the notorious Kilmainham Jail in Dublin. Shelley aims to meet with Devlin to learn more about Emmet, but Anne distrusts him and turns him away, because he is an atheistic Englishman, whom she believes fancies himself a reincarnation of Emmet.

While Shelley fails in his quest to free the Irish and learn more about Emmet, Harriet befriends Anne Devlin and learns her story. Harriet, who claims to possess an Irish soul, discovers in Anne’s story what genuine courage means when confronted by evil and injustice, but will she be brave enough to withstand her own encounter with English tyranny?

Another side note – when I was a professor at NIU, I taught in our study abroad program in Dublin and learned about Anne Devlin and even visited where she was confined in the dark in Kilmainham Gaol. I’ve wanted to write her story for a very long time so that American readers, especially those of Irish descent, would learn about her fortitude and bravery. When I was researching material used in Vindicated, I learned about Percy’s naïve attempts to “free” the Irish. So, it seemed natural to me that he might meet Anne Devlin in 1812, a few years after she was freed from Kilmainham.

KW: Thank you, Kathleen, for your generous answers to my questions! To learn more about Vindicated: A Novel of Mary Shelley, click here.